-

Winter 2026: Financial Technology and Innovation

Technology continues to advance at an unprecedented pace, with innovations including AI dominating public discourse…

-

Improving the Federal Budget Management Process

This report examines how federal agencies can improve budget management through business process reengineering, modernized…

-

2025 CFO Survey Report Series: CFO Priorities for Advanced Technology Adoption

AGA and Guidehouse’s 2025 CFO Survey explores how government financial leaders are navigating AI adoption.…

-

Fall 2025: Celebrating 75 Years of AGA

This issue’s special theme, Celebrating 75 Years of AGA, inspired a variety of interesting and…

-

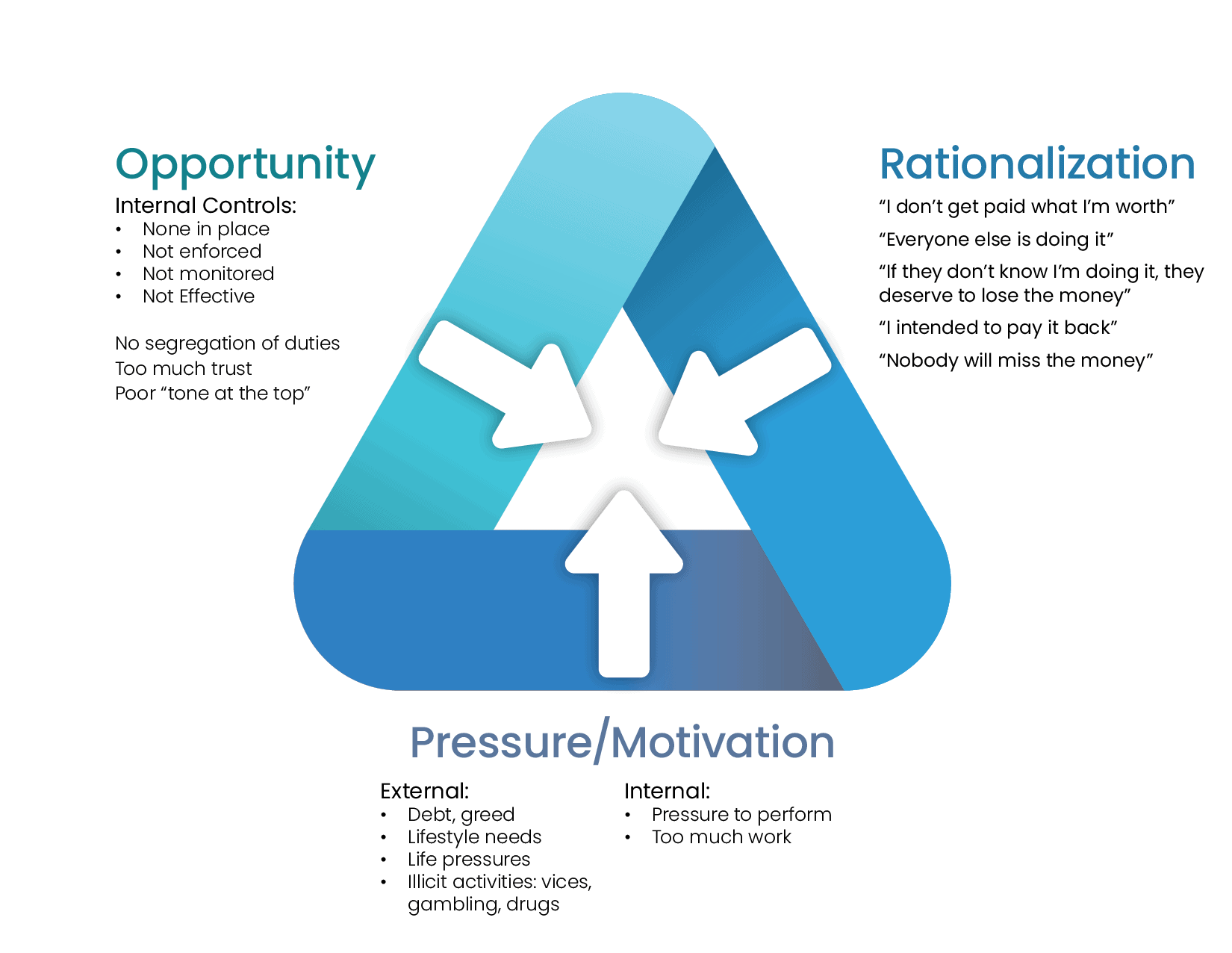

The Fraud Triangle

To fight fraud one must not only realize that it occurs, but also how and…

-

2025 Performance Counts Report

AGA has released its 2025 Performance Counts report, highlighting insights from a critical summit on…

-

CFO Survey Report 2025

AGA, in collaboration with Guidehouse, introduces the latest edition of its CFO Survey Series, entitled…

-

Summer 2025: The Government’s Fiscal Condition

The summer edition of the Journal of Government Financial Management theme, “The Government’s Fiscal Condition,” inspired a…

-

An Independent View of DOD Challenges from the Vendor Community

This report is the second in a series created by AGA’s Corporate Partner Advisory Group…

-

Spring 2025: Preparing for the Future of Government

With fewer available accountants, how can organizations best attract and retain financial management staff? How…

Become a CGFM

Learn the value and benefits of becoming a CGFM.